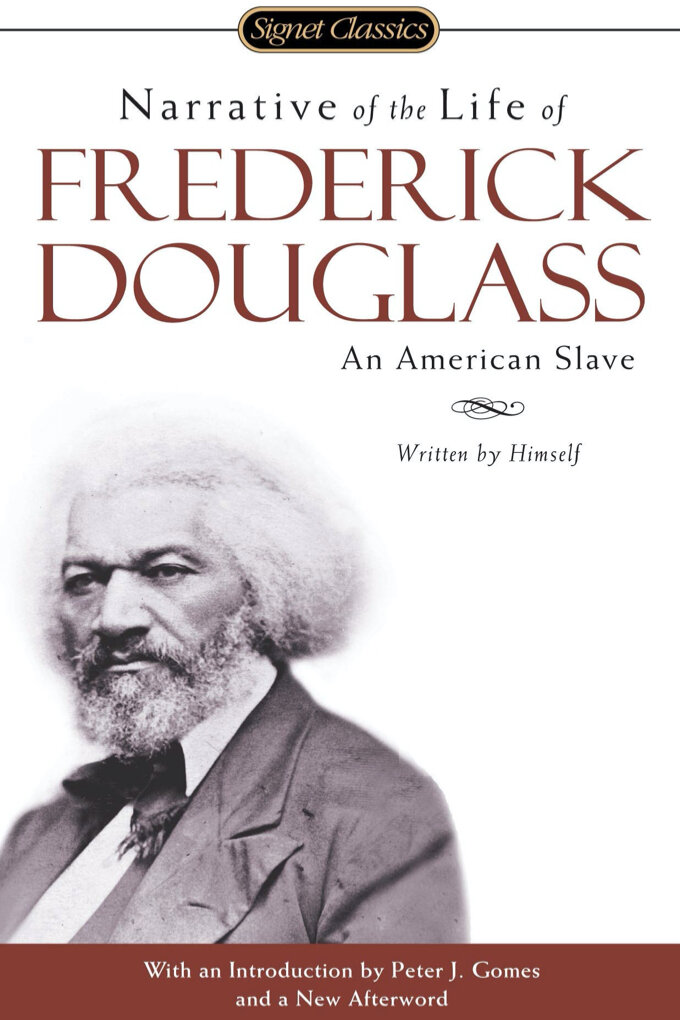

By Frederick Douglas

Why should one read the narrative of a former slave now dead 125 years? Because Douglass puts faces on facts, showcases the brutality of slavery, and demonstrates the power of the human spirit to overcome both oppressors and oppression.

In Frederick Douglass we see a microcosm of slavery, our national blight. We discover the evils of bondage, but also the way out. Douglass examines slavery personally, but also theologically, philosophically, theoretically, and practically.

Frederick Douglass wrote three accounts of his own life in addition to other writings, editorials and speeches:

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself (1845)

My Bondage and My Freedom (1855)

The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881, rev. 1892)

What stands out about the Douglass narrative is that he wrote it about the age of twenty-seven. Recently free and with little education, Douglass's words are clear, crisp, and compelling.

The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself recounts his life from his birth in 1818, through his early slavery to the events that led to his determination to escape, to his freedom, work as a caulker in the Baltimore shipyards, and marriage to Anna (1838). In weaving his account Douglass describes the cruelties of slavery; a chattel lifestyle of poor conditions, hard labor, intimidation, subsistence diet, and whippings should the slave object, question, or step out of line.

Douglass puts faces on the facts of slavery. It was dehumanizing:

Colonel Lloyd: Douglass went to live on the Lloyd plantation at 6 years of age. "I suffered much from hunger, but much more from cold. In hottest summer and coldest winter, I was kept almost naked--no shoes, no stockings, no jacket, no trousers, nothing on a but a coarse tow linen short. I had no bed. . . . Our food was coarse corn meal boiled. This was called mush.. The children were called to feed on it like pigs. (p. 54)

Aunt Hester:"Now, you d____d b____h, I'll learn you how to disobey my orders!" Master Anthony stripped her bare to the waist, tied her hands above her head and whipped her till the blood poured. Her offense? She was not their for Anthony's pleasure one evening when he desired to use her. (p. 41-43)

Mr.Severe, the overseer for Captain Thomas Auld: Mr. Severe was rightly name: he was a cruel man. . . . From the rising till the going down of the sun, he was cursing, raving, cutting, and slashing among the salves of the field, in the most frightful manner." (P. 45)

Mr. Gore: The overseer for Colonel Lloyd: "He spoke but to command, and commanded but to be obeyed; he dealt sparingly with his words, and bountifully with his whip, never using the former where the latter would answer as well." (p. 51) Gore also murdered the salve Demby for refusing to be whipped (p. 52)

Thomas Auld, the slave owner with whom Douglass lived from 1826-1827 and then again in 1833: (pp. 134-141).

Douglass dispels the myth of the happy singing slave. "Every tone was testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains. The hearing of those wild notes always depressed my spirit, and filled me with ineffable sadness. . . . To those songs I trace my first glimmering conception of the dehumanizing character of slavery. . . . The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears." (p. 47)

Douglass highlights two keys that unlock the door of slavery: (1) Douglass lived in the Hugh's family for about seven years. During that time Mrs. Huges began to teach Frederick to read and write. Though her kindness turned to meanness, she provided the initial education that helped construct the ladder with which he climbed out of the pit of slavery. (2) Douglass obtained a a copy of "The Columbian Orator." He read it over and over. "They gave tongue to interesting thoughts of my own soul . . . . The moral which I gained from the dialogue was the power of truth over the conscience of even a slaveholder." (61)

Douglass, a Christian, chastises the Christianity of the South:Whether it is hypocritical behavior masked behind piety (p. 68), or misusing Scripture (p. 70), or the blatant bondage by those who preach freedom in Christ, Douglass pours out his thoughts on "the Christianity of this land, and the Christianity of Christ" in the Appendix. (pp. 104-107)

There is so much to appreciate in this brief narrative. Obviously, the case against slavery is the greatest, but there also is much to learn from Douglass about communication -- he was a master of it. (See page 126).

A strong reference list (annotated), additional writings, index, Douglass Chronology (18118-1895), and selected bibliography make the Bedford Books In American History edition I own particularly helpful. The unabridged Audible edition is a delight.

Here are a few quotes to ponder:

1. About Frederick Douglass:"There is him that union of head and heart, which is indispensable to an enlightenment of the heads and a winning of the hearts of others." William Lloyd Garrison, abolitionist and early friend and supporter, 1845. (p. 31)

2. About the myth of the happy slave: "A happy slave is an extinct man." Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrision (p. 33)

3. About the price of freedom: "In coming to a fixed determination to run away, we did more than Patrick Henry, when he resolved upon liberty or death. With us it was a doubtful liberty at most, and almost certain death if we failed. For my part, I should prefer death to hopeless bondage." (86)

4. About the reality of the precarious position of slaves: "They say the fathers, in 1776, signed the Declaration of Independence with the halter about their necks. . . . In all the broad lands which the Constitutions of the United States overshadows, there is no single spot, -- however narrow or desolate,-- where a fugitive slave can plant himself and say, "I am safe." Wendell Phillips, Esq. (p.37)

5. About the blindness of those who profess religion: Their blindness is but one form of that prevalent fallacy which substitutes a creed for a faith, a ritual for a life." In Margaret Fuller's review. (p. 123)